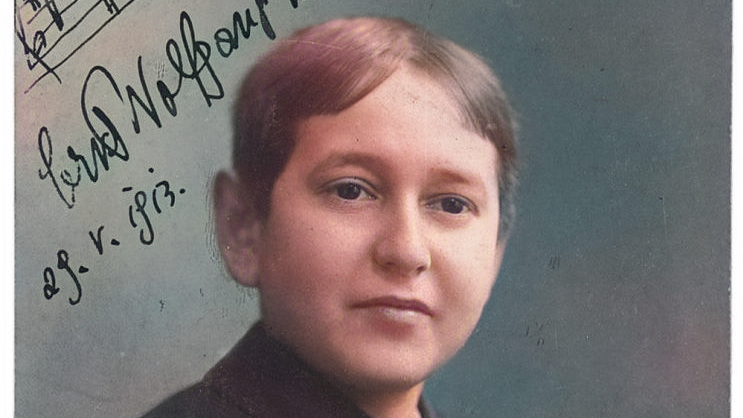

Erich Wolfgang Korngold is often associated with the creation of the symphonic film score. Indeed, many of his admirers today became familiar with his music through his film scores of the 1930s and 1940s. But before arriving in Hollywood he was a well-known composer of concert and chamber music, operas and stage works, as well as an arranger and conductor. Though most often compared to Mozart himself, Korngold was, in his own right, one of the most gifted composing child-prodigies in the history of music. Erich Wolfgang Korngold was born into a Jewish home in Brünn, Moravia (today known as Brno, The Czech Republic) on 29 May 1897 as the second son of Dr. Julius Korngold and his wife Josefine. He grew up in Vienna from the age of four, when his father assumed the position of music critic at the Neue Freie Presse (New Free Press) newspaper as successor to the noted reviewer Eduard Hanslick.

Already having played the piano from a very early age, the young prodigy composed his first original works in 1905 at the age of eight. Demonstrating a phenomenal musical precocity towards music, Korngold was taken by his father in 1906 to meet and play for Gustav Mahler. Proclaiming the child a genius, Mahler encouraged the elder Korngold to engage the renowned composer Alexander von Zemlinsky as the boy’s mentor. Though there were lessons with Robert Fuchs and Hermann Grädener among others, for all intents and purposes Zemlinsky would be Korngold’s only teacher, and for only a short time at that.

Julius Korngold published privately three of his son’s compositions in 1909 – the ballet “Der Schneemann” (The Snowman), the Piano Sonata #1 in d minor, and the character study suite “Don Quixote” – and distributed them to dozens of musical authorities, inlcuding Artur Nikisch, Englebert Humperdinck, Hermann Kretzschmarr, and Richard Strauss among them. All who examined the scores expressed amazement at their originality. Strauss in particular singled out their bold harmonies and assurance of style.

Not long after, the two-act ballet/pantomime Der Schneemann introduced the young wunderkind to the world with two premiere productions in 1910. The first, a performance in April at the ministerial palace of Baroness von Bienerth, employed a four-hand piano arrangement with the young composer at one piano, and Richard Pahlen at the other. The second, in October, presented an orchestral arrangement of the ballet premiered by imperial decree at the Vienna Hofoper on Emperor Franz Josef’s name-day. The sensation was followed in November by the Munich and New York premieres of his Piano Trio, Op. 1. Astounded by the abilities of this “miracle child”, the musical cognoscenti of the time were quick to take up and promote the creations of this musical wunderkind.

In 1911, Artur Schnabel premiered (and afterward championed extensively) the Piano Sonata #2 in E Major, Op. 2. The same year also saw Artur Nikisch give the world-premiere at the Leipzig Gewandhaus of Korngold’s first orchestral work, the Schauspiel Ouvertüre, Op. 4, displaying the composer’s gift for orchestration. In 1913, the Sinfonietta in B Major, Op. 5 – a symphony all but in name – was premiered in Vienna under the baton of Felix von Weingartner, and the Violin Sonata in G Major, Op. 6 was premiered by Karl Flesch and Artur Schnabel in Berlin, fully demonstrating the composer’s range of mastery from the large late-Romantic orchestra to the virtuosic intimacy of smaller-scored chamber works.

The 19-year-old Korngold became a respected opera composer in 1916 with the instant success of his two one-act operas, Der Ring des Polykrates and Violanta under the baton of Bruno Walter in Munich. The Vienna premiere shortly after presented the singer Maria Jeritza as Violanta, who would later take the lead role in the premiere of Korngold’s third opera Die tote Stadt at the Metropolitan Opera in 1921. In 1917 the Rosé Quartet premiered the Sextet for Strings in D Major, Op. 10 in Vienna. The year 1920 saw the incidental music for a production of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, and the double world-premiere in Hamburg and Cologne of Korngold’s operatic triumph, Die tote Stadt (The Dead City). The libretto was based on Georges Rodenbach’s novel “Bruges-la-Morte”, written secretly by Korngold and his father, but using the pseudonym Paul Schott – “Paul” for the main character of the opera and “Schott” for the composer’s publisher. (The secret was so well kept that it was not until well after Korngold’s death that the truth of authorship was discovered.)

After having gained experience as music director/conductor at the Stadttheater Hamburg, Korngold added arranging and adaptation to his impressive resumé with an arrangement of Johann Strauss’s Eine Nacht in Venedig for the Theater an der Wien in 1923. During the next several years he would continue to arrange operetta, as well as compose original works (the String Quartet #1, Op. 16, the one-movement Concerto for Piano Left Hand commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, and the Three Songs, Op. 18 all date from this period), while still maintaining his position as a conductor.

The premiere in 1927 of Korngold’s fourth opera, Das Wunder der Heliane – which he considered to be his most important work – in opposition to Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf was not as successful as his previous operas, giving Korngold a taste of disappointment as Jonny became opera of the year. Despite a stellar production that included Lotte Lehmann and Jan Kiepura in the leading roles, the interest of the Viennese public in Korngold’s once “progressive” music, began to wane in favor of other styles considered more “modern”.

Continuing undaunted in his various endeavors, however – now with the additional title of Professor at the Vienna Academy of Music – Korngold collaborated with Max Reinhardt in 1929 on a new production in Berlin of Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss. This same period saw the premiere of his Suite for Two Violins, Cello and Piano (Left Hand), Op. 23, and his third Piano Sonata, Op. 25. In 1932 the world received the premiere of the Baby-Serenade, Op. 24 in which Korngold, for the first time, incorporated jazz elements in his style. That same year he began work on his fifth opera Die Kathrin.

In 1934 at the request of Max Reinhardt, who was already working in the United States, Korngold came to Hollywood to arrange Mendelssohn’s incidental music for Reinhardt’s film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. One year later during his second stay in America, Korngold composed film scores for both Paramount and Warner Bros. Shortly after, he signed an exclusive contract with Warner Bros., making him one of the first world-renowned composers to work for the Hollywood film factory. His first original score for Captain Blood helped launch Errol Flynn’s film career in 1935, and Korngold’s score for the movie Anthony Adverse received an Oscar for the best film music of the year 1936.

Though under contract with Warner Bros., Korngold was living between two worlds, composing film scores in Hollywood, but attempting to maintain his concert and opera presence in Europe. In 1938, the “Anschluss” of Austria by the German National Socialists took the Korngolds by surprise. To save his family Korngold moved them to the US, choosing to write film scores regularly, and essentially vowing not to compose concert works again until Hitler was removed from power. His first movie score as an exiled resident in the New World – The Adventures of Robin Hood – earned him his second Oscar. Until 1946 Korngold composed mainly film music, using his income to support many friends and refugees fleeing the tyranny in Europe. Together with Max Steiner, he stood for a new music style in Hollywood, in which his highly illustrative but independent music partly intervened in the story of the film by expressing atmosphere, and simultaneously utilizing the Wagnerian concept of leitmotifs. Some of the movies he scored include The Prince and the Pauper (1937), Juarez (1939), The Sea Hawk (1940), The Sea Wolf(1941), Kings Row (1941), and Deception (1946).

Beginning essentially in 1946 with the premiere of the String Quartet #3, Op. 34, Korngold said goodbye to the Hollywood film industry and attempted to return to the concert platform and the composition of absolute music. Deftly borrowing themes and motifs from his many movie scores – a key provision in his contract with Warner Bros. – Korngold produced the Cello Concerto, Op. 37, the Violin Concerto, op. 35 (premiered by Jascha Heifetz in 1947), and the Symphonic Serenade, Op. 39.

Deciding to return to Europe in the fall of 1947, plans were indefinitely delayed when Korngold suffered a heart attack on 9 September 1947. The aging composer finally set foot in Austria in 1949 for the first time since before World War II. In 1950, under the direction of Wilhelm Furtwängler, Korngold’s Symphonic Serenade in B Major, Op. 39 was successfully premiered by the Vienna Philharmonic. Other performances of his works, however, were poorly attended, and the critic’s reviews were not favorable – the Viennese public’s musical tastes had moved on in Korngold’s absence. The following year Radio Wien premiered his musical comedy Die stumme Serenade, again with less than favorable results. Korngold found himself forgotten and unappreciated in his former homeland, and with the effects of the war on Vienna, the world he once knew was gone forever. He returned to America disappointed and dejected, believing his fame and position were fading before his very eyes.

He returned a second time to Europe in 1954, at which time his Symphony in F#, Op. 40 was premiered. Attributed to lack of preparation, the radio premiere was less than successful. Following a second disappointment with the failure of a production of Die stumme Serenade, he traveled to Munich under agreement with Republic Pictures to work on one last film, Magic Fire, a biography of Richard Wagner. Fearing that in less devoted hands the music of Richard Wagner would be ill-represented on the movie screen, Korngold had decided to return from retirement and oversee the arrangements of Wagner’s music for the film. It would be his last motion picture score.

In 1956 Korngold suffered a stroke, leaving him partially paralyzed. Then in 1957, at the age of 60 with a second symphony and a sixth opera planned, and with sketches begun, Korngold died on 29 November as the result of a cerebral thrombosis. Austrian by birth, a naturalized US citizen since 1943, child prodigy, renowned opera composer, film composer, arranger and conductor, Korngold died in Hollywood believing himself virtually forgotten. But in the late 60s, one single LP of his movie music conducted by Lionel Newman was released. It would be turn out to be that small crack in the dam that would continually widen, allowing more and more of Korngold’s music to pour out as the years progressed.

In the 1970s, under the watchful guidance of his younger son George, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s music was produced as part of a series of retrospectives LPs of the classic movie scores from the Golden Age of Hollywood, performed by the National Philharmonic Orchestra under Charles Gerhardt. Records of his chamber compositions and shorter orchestral works began to be released. New champions of his music emerged. And ever since, the recordings of his works – concert, stage and screen included – continue to grow in quantity as his music is rediscovered and appreciated by a younger, newer generation. Today his Violin Concerto is in the repertoire of many leading performers. With dozens of new recordings and live performances each year, Korngold’s star continues to rise, ensuring that his music will live on.

Troy Dixon

February 2006

Revised February 2011