In Preparation – Our feature on the Royal Conservatory’s world-premiere production of Korngold’s Silent Serenade in English.

In mid-November 2013, Troy Dixon traveled to Toronto, Canada to hear the world-premiere of the English-language version of Korngold’s only original operetta, The Silent Serenade.

Background

© Troy O. Dixon, December 2013

The Silent Serenade has a quite complicated gestation, which may partially explain its limited performance history, and its lack of any prior production in English. The plot-line comes from the adaptation of a short story by Raoul Auernheimer, the Austrian writer who succeeded Moritz Benedikt as editor of the Neue Freie Presse, and a colleague of Korngold’s father, the newspaper’s leading music critic, Dr. Julius Korngold. To adapt Auernheimer’s story, Korngold turned to Rudolf Lothar, a fellow émigré living in Hollywood who today is remembered as the librettist for D’albert’s Tiefland. Unsatisfied with the revisions and development, Korngold enlisted the Hungarian writer Viktor Clement to further revise the story and treatment. He commissioned William Okie, who produced English lyrics for the songs and ensembles. He also commissioned Bert Reisfeld for lyrics in German, and then had Auernheimer translate the entire English work – book and lyrics – back into German.

Having successfully produced two previous Korngold arrangements for Broadway – Rosalinda (1942) and Helen Goes to Troy (1944) – the New Opera Company was the logical first choice to approach for staging his original operetta, The Silent Serenade. In May 1946, the Company held an audition for potential backers, at which the plot outline was read and several songs were sung. Ultimately a production never materialized. By October 1946, during a trip to New York, Korngold expressed his disappointment: “To get a performance in New York, music has to be ugly, programmatic, serious. If it’s beautiful it is only tolerated if the composer has been dead for fifty years.” [1] His expression of disappointment may possibly result from the failed New Opera Company efforts, combined with the scheming and plotting of the Shuberts to obtain production rights to the operetta. [2]

The Shubert brothers, Sam, Lee and Jacob J., laid the foundations for a theater management company prior to Sam’s untimely death in 1905. By 1916 Lee and Jacob Shubert had become the nation’s most important theater owners and managers, and by the start of the Great Depression they owned, operated, managed or booked over 1000 houses in the US. According to Korngold biographer Brendan Carroll, the agent and artist manager Paul Gordon (Viktor Clement’s brother) arranged for Jacob Shubert to hear Korngold perform his new operetta himself. Shubert decided to present it immediately after hearing it. In a letter from George Korngold to Mr. Carroll, the composer’s son recounts: “’When the contract arrived, it contained clauses that gave Shubert full control over the orchestration, libretto and so on. My father refused to sign and Shubert, not used to being rejected, went to Viktor Clement and offered to option the libretto on its own if he would split it from the music. …[F]or nearly two years, book and music were separated, while Shubert had one score after another written for it. When nothing was produced that came anywhere near the quality of Korngold’s score he finally gave up and gave it back to Clement.” [3]

By September 1947 the Shuberts were well into production planning, trying to get writers and composers to replace Korngold’s score. Writers included Fred Jay and Irving Rifkin for lyrics, and Denes Agay was one of the composers approached. A surviving letter from the composer Emmerich Kálmán to Korngold indicates that he, too, was approached to compose music for the production, but refused. [4]

Korngold had planned to return to Europe in 1947, but was delayed when he suffered a heart attack in September of that year. Eventually traveling in 1949, he decided that The Silent Serenade would make a good production for his European “comeback.” Mr. Carroll states that Korngold was busy with endless calls and cables regarding the German version, Die stumme Serenade, while preparing for Furtwängler’s premiere of his orchestral work, Symphonic Serenade, Opus 39, scheduled for 15 January 1950. [5] Specific dates are unavailable, but it would seem logical that Reisfeld’s German lyrics, and Auernheimer’s translation of the English The Silent Serenade into German would have happened sometime between 1947 and 1949, after an American premiere failed to materialize.

The work was finally performed for the first time as a live broadcast production for Vienna Radio on 26 March 1951. Not long after, Korngold left for America, with no plans to ever return to Europe. After arriving back in Hollywood, he began reworking The Silent Serenade to make it stageable. Finding himself in Europe once again in 1954, despite his determination to remain in America permanently, Korngold took a break from his work on the film “Magic Fire” to prepare the first staged production of The silent Serenade. The premiere took place in Dortmund on 20 December 1954, with a series of poor reviews following. Brendan Carroll characterizes the failure as a result of the work’s “curious blend of opera, operetta and revue (some of these catchy tunes would not have been out of place in the Berlin revue cabaret of the late 1920s),…[making it] already old fashioned and out of step with the musical theater of the time [in 1954].” [6] After Dortmund it remained unperformed until 2007.

Notes

[1] “He’s Fed Up With Music For Films.” New York Times, 27 October 1946.

[2] Specific dates for the start of the Shuberts’ involvement are not available, but by the middle of 1947 they were apparently well underway with their own plans to produce a version of Korngold’s operetta, implying that they entered the picture months earlier.

[3] Letter quoted in Brendan Carroll’s liner notes to the CPO recording of “Die Stumme Serenade”.

[4] Letter from Emmerich Kálmán to Erich Wolfgang Korngold, New York, 4 April 1947, quoted in Clarke, Kevin. “Der Walzer erwacht die Neger entfliehen: Erich Wolfgang Korngolds Operetten (bearbeitungen) von Eine Nacht in Venedig 1923 bis zur Stummen Serenade 1954.”

[5] Carroll, Brendan. The Last Prodigy. p. 341.

[6] Brendan Carroll’s liner notes to the CPO recording of “Die Stumme Serenade”.

The Story

The plot concerns a dressmaker, Andrea Coclé, who is secretly in love with a famous actress, Silvia Lombardi, fiancée of Prime Minister Lugarini. On the same night that an amorous intruder attempts to abduct Sylvia from her bedroom, a bomb is planted under the bed of the Prime Minister. The following day’s investigations lead to Sylvia’s couturier, Coclé, secretly in love with her, who admits to being in her garden the previous night, to serenade her – silently, of course.

The incompetent and bumbling Chief of Police convinces Coclé to admit to both crimes of attempted abduction and planting the bomb, with the promise of a royal pardon to mark the King’s 80th birthday. Unfortunately, the King dies before signing the reprieve.

With the King’s death, Lugarini becomes Regent, seemingly all but sealing Coclé’s fate. However, due to Coclé’s popular appeal with the citizenry (and with much confusion), he is exonerated and reunited with Silvia who, by then, has realized that he is the man she really loves. Her engagement to Lugarini is broken, Lugarini is deposed, and Andrea and Sylvia (presumably) live happily ever after.

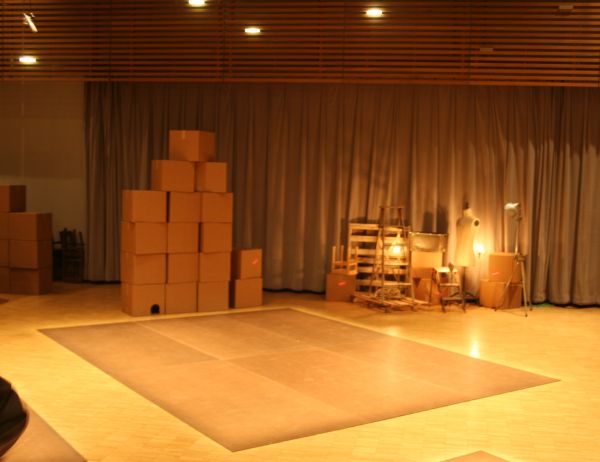

View of the main staging area for the production (below). Photos by Troy Dixon.

Page last updated January 201