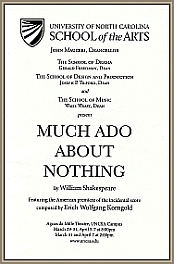

From 29 March to 7 April 2012 the University of North Carolina School of the Arts presented William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, featuring the American premiere of the incidental score composed by Erich Wolfgang Korngold. This page presents information related to that landmark production, inlcuding original press releases, links to radio interviews, and reviews and commentaries by the Korngolds, who attended the opening night performance, and by Troy Dixon, who attended the last day performances.

Update: UNCSA’s production received a Regional Emmy Award in January 2014 – see below.

Background on the theater genre

The following is adapted from a radio interview with John Mauceri, presented by Triad Arts Up Close on WFDD radio 88.5 FM, Wake Forest Univesity, North Carolina, US. Used with permission.

“One of the things that makes the Much Ado About Nothing production at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts so special is that we’ll be giving people an experience that has not been accessible anywhere in the world for maybe 80 years. That experience is to go to a play – not a musical, not an opera, not a ballet, but a play – and there’s an orchestra in the pit that plays an overture, and then the curtain goes up and people talk. They don’t sing – they talk. And at certain points in the play the music from the orchestra pit describes a scene change, or underscores a particular dialogue scene, or characterizes somebody who walks on or off the stage like a leitmotiv technique from Wagner.

“This type of theater experience was an equal partner in the great theaters of Europe where one third of the year was ballet, one third of the year was opera, and one third was theater. The big theater houses had orchestras on contract, so composers were writing music to accompany the great epic plays, whether that’s Beethoven for Goethe’s Egmont (music composed in 1810), or Schubert with Rosamunde (1823), or Mendelssohn for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1842), or right up through Sibelius whose last greatest work is The Tempest (1926). Even Haydn’s Symphony No. 60 in C major, Il distratto (“The Distracted One,” composed by 1774) was actually cobbled together by Haydn from music that he wrote to a comedy called Il distratto – so Haydn was part of this theater genre also. So we see the history of this tradition, but no one can experience it anymore.

“When most people think of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, they think of an orchestra performing it. For example, a few years ago the Winston-Salem Orchestra performed the play – cut down – with students from the School of the Arts that gave the audience some idea of how the music worked with the play, but they were still looking at an orchestra on the stage, not watching a play on stage with orchestral support. Imagine hearing the overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and then the curtain goes up and we’re hearing the words of Shakespeare. Now that’s what used to happen.

“All of this eventually became movie music, by the way, because the composers who were ultimately successful in creating the sound of Hollywood and how music works in dramatic movies were the composers who were trained in this very style of theatrical music that was part of a centuries old tradition in Europe. And we have to say Europe specifically because American composers had never seen anything like this because we didn’t have that same tradition in the United States of America. But a Max Steiner, or an Erich Wolfgang Korngold, or a Miklós Rózsa, or a Dimitri Tiomkin, or any of those first, hugely successful composers in the era of sound films from the 1930s knew this tradition well, and they understood what the gestures were. The gestures come out of Wagner, of course, and they come out of a history of which Wagner is really the most important, but which continued on to Richard Strauss and Mahler. But before them was Beethoven and Schubert.”

John Mauceri, interviewed by David Ford