Simone Trovai Wolfgang Schöne

Violanta Eiko Senda Scenic

Alfonso Evan Bowers

Giovanni Bracca Enrique Folger Costume Design Imme Möller

Bice Monica Philibert Chorus Director Peter Burian

Barbara Alejandra Malvino

Teatro Colón Orchestra

Matteo Osvaldo Peroni

Music Director Stefan Lano

Teatro Colón Chorus

Direction Hans Hollmann

Lighting/Scenery Design Enrique Bordolini

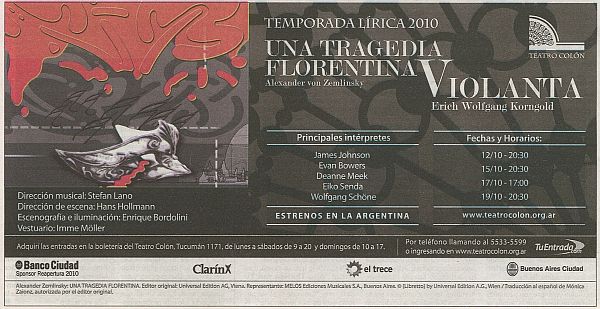

This year saw the Argentine premiere of operas by two late Romantic composers who have been experiencing renewed interest in their works. On October 12th the world famous Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires presented a gala premiere of Alexander von Zemlinsky’s Eine florentinische Tragödie and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Violanta. The productions of these operas were unarguably very good, but with a few specific reservations.

At first glance, this coupling may seem unusual – apparently Eine florentinische Tragödie is more typically paired with Der Zwerg for an all-Zemlinsky affair – but this same Zemlinsky/Korngold double-bill was presented in 1984 by the Santa Fe Opera in the US. Reviewers of the Argentine premieres have been quick to point out commonalities and parallels to justify their paired presentation. Included in the list of similarities have been such observations as:

Both operas are by German composers

Both operas are set in Italy during the Renaissance: Florence (Zemlinsky) and Venice (Korngold)

Both are one act operas

Both had their world-premieres within a year of each other: 1916, Munich (Violanta) and 1917, Stuttgart (Tragedy)

Both involve a love-triangle with a tenor coming between a baritone and a soprano

Both were deemed “Entartete” by the Nazis

Not stated by other reviewers, but equally mentionable, both operas are products of an earlier Viennese decadence that at the time of composition was realizing a more menacing Renaissance that mirrored the growing dark times of the early 20th century. Both operas also employ vengeful Italian characters of violent colors and nervous passions. Reviewers also frequently note the personal relationship between Zemlinsky and Korngold, and one even mentions that both composers stood apart from the atonal, twelve-tone methods emerging at the time of their premieres. Presumably it is this extensive set of similarities that prompted Hans Hollman (scene direction) and Enrique Bordolini (scenery and lighting design) to use the same set design for both operas, with only minor changes: different rear-projection scenes to emphasize in which city the action takes place, different portraits on the center wall, and minor changes of props.

The orchestra under Maestro Stefan Lano played well for an ensemble that was reported by one local newspaper as “..certainly far from its best periods.” (Anyone unfamiliar with the orchestra would have had a very hard time discerning that particular anomaly.) The overture to A Tragedy set the mood for the evening: the audience was in for a special treat. The music to both operas was done well in general, though the overall volume sometimes obscured the singers’ voices, and the blend of individual instruments – especially in the Korngold – was periodically “off”, with horns standing out a little too much in spots, various woodwinds in others, etc. Aside from a somewhat under-paced overture for Violanta, however, tempi accentuated and heightened the action quite well.

The singers did a wonderful job in interpreting both of these operas. Of the Violanta production, Eiko Senda in the title role sang beautifully, though her acting may not have been at quite the same standard. Tenor Evan Bowers performed marvelously in both operas (Alfonso for Violanta and Guido Bardi in A Tragedy, seeming perhaps a bit more comfortable as the former), and baritone Wolfgang Schöne as Violanta’s husband performed his part excellently. Though small, the choir’s part in Violanta was executed solidly, conveying the presence of a larger throng just outside the interior space of the palace. The smaller roles were also performed very well.

The first word that springs to mind to describe the staging is appropriate. While use of the same set for both operas might be perceived by some as flawed, since the cloth merchant Simone in A Tragedy is not the owner of a mansion, while Violanta’s husband, Venetian military commander, is well above middle class, the realm of live theater rarely strives for exact representation, frequently favoring “suggestion” over exactitude. With opera a heightened form of live theater, the same approach (i.e., “suggestion”) is more than viable. So in this sense the same set in a darkened light served quite well in representing the home of a merchant in A Tragedy, while the multitude of characters and periods of increased lighting in Violanta easily suggested a better class (dare we use the word “wealthier”?) environment.

The color red predominated throughout both productions, ostensibly to signify at the same time both the passions and the blood/murder aspects of both stories. Dresses for both female leads were red, as were set curtains and periods of lighting. Other themes might have been equally successful, but this particular treatment was altogether acceptable.

Even though many opera productions are frequently staged today in updated settings, the 20th century costumes here were a bit puzzling given the supposed Renaissance setting of both stories. However, even after one made this observation at the start of the opera, the costuming fortunately did not distract or detract from the presentation.

Overall, a commendable presentation for the re-opening season of Teatro Colón following several years of renovation work.

Violanta, October 2010: The Buenos Aires Premiere

A Personal Reflection by Troy O. Dixon

From New York to Buenos Aires is 5300 miles (8500 km). All that way to see an opera? Irrational? Absurd? (The late poet Turner Cassity might have been proud.) But the rarity of a staging of Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Violanta seemed to demand a trip, and in the end I think it was well worth it.

Four days of perfect weather with not one cloud in the sky and daily temperatures of about 72°F (22°C) were just right for a first time visitor to explore and get acquainted with both Buenos Aires and its people. I found my short time there not quite adequate to fully appreciate the area and culture, but sufficient enough to open the cover on the rich history of this South American metropolis. Curiosity piqued, a future return visit makes a pleasant prospect. And while knowledge of Spanish would have been immensely helpful (my training was in German), it was not impossible to get around and interact with the local population. I suppose tourism prevails enough, as a good percentage of the people have at least a rudimentary English vocabulary.

My anticipation to experience Violanta in a live production grew steadily as day four arrived and evening slowly approached. And being able to see the newly reopened Teatro Colón while at the same time witnessing the Buenos Aires premiere of these two operas was an additional treat I will treasure. The productions did not disappoint.

Zemlinsky’s one act opera Eine florentinische Tragödie was presented first, followed post-intermission by Korngold’s Violanta. For Korngold fans new to the city, it was a perfect sequence, giving us a chance to get familiar with the famous theater and its orchestra prior to hearing Korngold’s first tragic/dramatic opera. Less familiar with A Tragedy, it was nonetheless a marvelous production, providing added dimensions to the music I am acquainted with through recordings. And seeing Violanta brought to life (there are no video recordings of this opera of which I’m aware) was wonderful for this particular Korngold-fan.

Iinterestingly, the age of the theater was near-palpable if one chose to pay attention. Sitting in the century-old auditorium, with its old-world style and historic atmosphere, I had a sense of what it must have been like to experience the premieres in 1916 and 1917. Despite a staging that was surely more modern than that produced during the World War I era, this might have been as close to feeling like being at the premiere as one can have, especially since the Munich opera house where Violanta premiered was destroyed in 1943 during World War II by bombing raids.

Both operas received well-deserved ovations from those in attendance. Cast and crew did an excellent job in bringing these works of art to life. Hopefully I will have a chance to see Violanta producted again. If not, I will be very happy with the memories of Teatro Colón’s premiere production.

Teatro Colón is a marvelous edifice with an interesting history. The 2500-capacity theater along Av. 9 de Julio (technically Cerrito Street), fronts on Libertad Street at the corner with Tucumán Street. It is actually the second theater in Buenos Aires to bear the name “Columbus Theater”, the first having been closed around 1888.

Shortly after the first theater shut its doors, the Italian architect Francisco Tamburini was selected to design the present theater as a replacement. Beginning with his death in 1891, the theater’s design was passed first to Italian architect Víctor Meano, and finally in 1904 to Belgian architect Jules Dormal following Meano’s death. Having been designed and redesigned several times by different engineers and architects of different nationalities, the resulting structure blends German, Italian and French styles, making it a unique architectural style of its own.

The theater was inaugurated on 25 May 1908, and featured a performance of Verdi’s Aida that evening. Among the composers that have directed or witnessed performances of their own works over the years include Stravinsky, Respighi, Saint-Saëns, Pietro Mascagni, Richard Strauss, Khachaturian, Copland, Pierre Boulez, Leonard Bernstein, Alberto Ginastera and Gian Carlo Menotti. In 1989 it was declared an historical monument, and in October 2006 it closed for major renovations and upgrades, reopening just this past year in May 2010.

The theater resembles the elongated horseshoe design of 19th century European theaters. Its seats are divided into three levels of boxes, two dress circles, and two upper circles, all above the main floor seats. Over the center is a magnificently painted ceiling, completed in 1966 by the argentine painter Raúl Soldi (1905-1994) to replace the original artwork by Marcel Jambon (1848-1908) that was destroyed by water damage in 1936. From the center hangs an enormous bronze chandelier, which together with 105 wall sconces illuminates the auditorium.

The 34,50m x 35,25m (113 ft x 116 ft) stage is one of world’s largest and is tilted slightly toward the audience – termed a “raked stage” – in the fashion of the times when it was originally constructed. It has a rotating disk in the center that can turn both directions to assist with scene changes. The cyclorama’s supporting track is 25m (82 ft) above the stage. The main curtain was manufactured in France, and originally took two liveried footman to work it. The orchestra pit can be raised to form a larger stage as required for concerts or productions. According to a publication in 2000, however, the most valued treasure of the theater are its acoustics. Many singers are reportedly shocked by the huge auditorium on their first visit. But the acoustics permit even soft sounds to be heard well, which finally calms the performers down.

Page last updated January 2011